by Harry McKenna (Level 3 History student)

Since he announced his candidacy for the Presidency in August 2015, Donald Trump has continuously provoked indignation with his comments about immigration and migrants that have been widely construed as racist, bigoted, and completely antithetical to American values and traditions. However, contrary to popular opinion, ethno-nationalism, a hostility to mass migration, populism, protectionism, and isolationism are traditions and sentiments dating back to the beginning of the USA’s founding as illustrated in the way the Naturalization Act of 1790 limited the naturalization process to ‘free white persons’. This article contextualizes Trump’s politics and rhetoric to illustrate that his form of politics is not unprecedented in US political history, and, most poignantly, that the apocalyptic fears and predictions regarding the Trump presidency from the Liberals are unwarranted and, when considering the history of US politics, exaggerated.

From the beginning of the 1800s American politicians have used the term ‘melting pot’ in the context of how America and the American identity represents a fusion of different nationalities, ethnicities, and cultures. However, it has been used with the stipulation that for any immigrant to be naturalized and be considered an American then they had to relinquish their previous culture and identity and conform unequivocally with the white ethno-nationalism that America was founded on. This is because as America experienced a rise in immigration in the 1800s there were fears that immigrants would distort existing cultural values and have divided loyalties. It is this demand for migrants to embrace American culture and to repudiate their past cultures in order to become legitimate Americans which pervades Trump’s rhetoric on Mexican and Muslim migrants and how they cannot be considered true Americans until they assimilate to American culture. In particular, the president has criticised migrants for refusing to learn English.

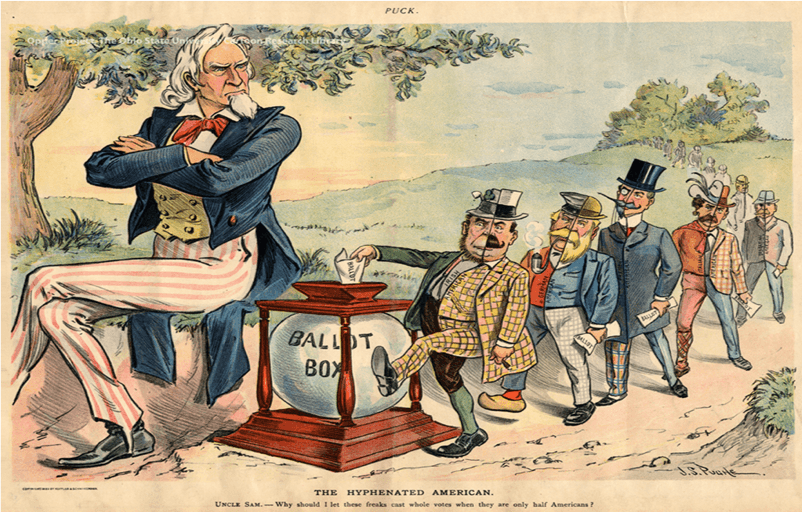

These sentiments became more pronounced and acute in the 1910s and 1920s as a consequence of the United States’ involvement in the First World War. It was widely believed that immigrant communities, branded as ‘hyphenates’, could not be trusted because their divided identities implied divided loyalties and supposed sympathies towards Germany. This was also an argument used to justify the internment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War, and contextualizes the separation policy that the US government is currently engaged in on the Southern border. President Wilson even went as far as to say that every American should ‘declare himself, where he stands. Is it America First or is it not’ – thereby endorsing the implementation of arbitrary loyalty tests on migrants living in America (specifically German-Americans) and encouraging Americans to terrorize their fellow citizens to cure them of any ‘un-American habits’.

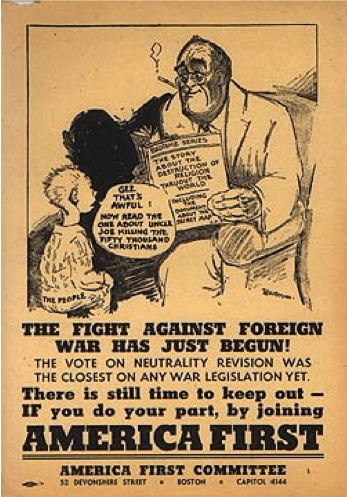

The arbitrary loyalty tests involved demanding migrants ‘to put themselves on the record as cherishing no loyalty to the country of their origin’ (behaviour which puts Trump’s comments about Mexican-American judges into much needed perspective). Furthermore, this ‘hyphenate hysteria’ caused immigrants to be branded ‘as impure, alloyed, defiling true Americanism with their suspicious foreign ways’ and was responsible for the emergence of the phrase ‘America First’ in popular culture. While this phrase also referred to a desire to keep America out of European wars and to an unwavering support for protectionist trade policies it ‘also strongly connoted…promises to protect “real” Americans from the threat of treachery by “hyphenate” Americans with supposedly divided allegiances’. This ethno-nationalism, anti-immigrant, and protectionist sentiment culminated in 1924 with the National Origins Act which introduced a quota system based on an immigrant’s origins meaning that immigration was reduced ‘by over 90 per cent, allowing visas to just 2 per cent of the total number of each nationality in the United States according to the 1890’s census’ with it being designed ‘to return’ America ‘to a nativist “whiter” past, when more immigrants were “Nordic”’.

The inconvenient truth regarding Trump’s rhetoric concerning immigration for contemporaries is that his attitudes and policies, in the context of American political history, are not unprecedented with there being stark similarities between the National Origins Act and Trump’s alleged preference for immigrants from white Caucasian nations over immigrants from Africa. America has a long tradition of creating ‘categories of racial superiority’ in its immigration policies. Furthermore, the National Origins Act and the recurring concern over immigrants having divided loyalties also illuminates how Trump’s efforts to protect America from individuals he perceives as having a natural disposition to inflict harm on Americans and erode its freedoms are not unprecedented. These efforts have manifested themselves in the implementation of a Middle East travel ban and in his refusal to permit the migrant caravan to cross the border until they have been vetted (to ensure they are actually seeking asylum and are not criminals) and followed the correct process, rather than border jumping, by deploying the military and using tear gas. Trump’s announcement that he wants to deny American citizenship to children of illegal migrants born in the USA, and discontinue the DACA program, is a further sign of the president’s desire to prevent the nature of American society changing irrevocably while challenging those who do not have a legal right to be in the USA. This is because the desire to protect Americans and the ‘spirit of America’ from individuals who may have ‘divided allegiances’ and behave in ways which threaten Americans pervades US political history, and has often manifested itself in strenuous, protectionist immigration policies. This is why Trump has expressed a desire to abolish sanctuary cities to prevent criminals who have entered America illegally from having refuge from immigration enforcement. Another explanation for why Trump and, historically, US politicians have been wary of mass migration is because they think it leads to a stagnation in wages, unemployment among American citizens and precipitates economic decline – something which Trump promised to reverse.

Trump has also used the phrase ‘America First’ in the context of the US’s overseas commitments, with him saying that the world can no longer expect America to be the world’s policeman and nor can it (or should it) be dependent on America for its security. Instead, Trump has promised to concentrate on rebuilding the USA’s economy (which he has succeeded in doing) and has withdrawn or re-negotiated the nation’s involvement in international agreements and organisations which he construes as being unbeneficial to US citizens and causing America too great a burden – this helps to explain his criticism of NATO and the Paris Climate Agreement. This also explains why he has committed to only engage in foreign conflicts which are in America’s interests, which is why he has decided to withdraw troops from Syria now that ISIS are on the retreat as he asserts it’s no longer in America’s interests to be involved in that conflict. This sentiment echoes that of the ‘isolationist Republicans’ in 1916 who insisted ‘we (America) should inflexibly resolve to keep out of entangling alliances, to fight our own war in our own way; to use American money and American men only for the defense of America’. This group’s mantra continued to be the ‘watchword of American foreign policy’ up until the Second World War as ‘a sense of sturdy independence had prompted the creation of the Republic in the eighteenth century, free from the control and influence of the European powers’. Consequently, Trump’s policies can be interpreted as an attempt to return America to its past of ‘sturdy independence’ so that other nations no longer have what he considers to be undue influence over America. Trump’s yearning to be free of ‘foreign entanglements’ is consistent with the anti-hyphenate xenophobia and nativism that has a long tradition in the USA: by avoiding foreign wars, ‘foreign entanglements’, and by leaving foreign nations to their own devices, the Trump administration is indicating that migrants and foreign nationals are not the priority and that they will not protect other nations or let migrants into the country at the expense of their own citizens, with them being committed to preserving American culture and security.

However, the slogan ‘America First’ has also been used historically in an internationalist context. This is because in 1916 Woodrow Wilson asserted that the phrase ‘was actually internationalist, meaning America should take the lead’ by ‘imparting to other people’s her own ideals of Justice and Peace’. This indicated his belief that the USA could serve as a beacon of hope and freedom for the world, with people aspiring to re-create American life in their own nations and one day reaching the land of freedom. This kind of American exceptionalism has been pervasive in US culture ever since the 1920s, with it being particularly prominent during the Cold War. Trump has even sought to co-opt older notions of American exceptionalism in claiming that the US should stand as a shining example to the world of how a society should be structured, of the rights that should be unalienable, and of what sort of lives people should aspire to and hope for.

To further illustrate that populism and the concerns Trump’s rhetoric and policies are tapping into have precedent in US politics, it is worth briefly exploring and dissecting the populist backlash America experienced in the 1970s which led to Ronald Reagan becoming President in 1981. In the early 1970s, the US experienced a series of events, in particular the fall of Vietnam to communism and the Watergate scandal, which damaged its psyche to such a degree that it precipitated a crisis of confidence and a sense of US decline. These events prompted a period of intense introspection for Americans whereby they questioned their place in the world and were anxious that the US was no longer a leading global power. The Arab oil embargo of 1973, where US citizens realised that the ‘world’s mightiest economy could be held hostage by some mysterious cabal of Third World sheikhs’, only served to reinforce these anxieties in the American consciousness because it illustrated that severe damage could be inflicted upon the US and its economic security by Third World nations. In the aftermath of this crisis of confidence amongst Americans two divergent perspectives on how to move forward emerged. One perspective was that an ‘education programme’ should be launched to educate Americans about the horrors that the US was allegedly responsible for and the idea that American power and influence over the world was not as innocent as they had been led to believe with the aim of making the American ‘a more humble and better citizen of the world’. However, the other opinion, expounded by Ronald Reagan, was that it was important to restore the American sense of self and that the US was innocent and a force for good, thus meaning that America should not be afraid of imposing its values on the world.

The individuals who wanted to educate people on how America’s actions were immoral believed the 1970s represented the perfect opportunity to launch this re-education of American citizens. This is because they could show the public that American intervention in world affairs did not always yield positive results. However, the media revealing that ‘the men entrusted with the White House’ were ‘little better…than common criminals’ also meant they thought people could be convinced it was not unpatriotic to ‘question leaders ruthlessly’. This perspective did not gain traction with the American population and represented a grave miscalculation of the public mood on their part. This perspective failed because the American public were simply not interested in listening to a perspective which, as aforementioned, contradicted everything they had been told, especially when they were grieving and mourning for the America they had known. Consequently, the American public rejected this message and turned to a candidate in Ronald Reagan who promised to restore American prestige in the world and who pampered to their belief system than America was a force for good in the world. By having a sense of ‘simple moral clarity’ and by ‘skilfully reframing situations…as crystalline black-or white melodramas’ Reagan ‘foreclosed that imperative’ – the idea being that Americans needed to grow up and question their leaders and become more sceptical – and ensured that a greater cynicism about US power never became prevalent in the minds of Americans from the 1970s to the 1990s.

In this conflict the voices advocating for a more critical perspective of American power were perceived as unpatriotic, while the optimistic voices were framed as true Americans. The consequence of this was that people, especially in Middle America, were consciously, and subconsciously, discouraged and dissuaded from voting Democrat because they did not want to help advance, what they interpreted as, the anti-American agenda of the left. Accordingly, this conflict had great and far-reaching ramifications on the left and their electoral prospects. There are stark similarities here with Donald Trump. This is because the 2016 campaign came at a time of introspection for America, with the US questioning its place in the world in response to the financial crisis of 2008 and the disastrous and ambivalent foreign policies of George Bush and Barack Obama respectively, which had created the perception amongst many Americans that US influence had receded. Consequently, they looked for a leader who promised to re-establish America as a geopolitical superpower (something that was needed after Iraq and Afghanistan). However, more poignantly, the American public sought a leader who would restore US self-confidence and who would allow them to indulge in their propensity for unabashed patriotism without feeling ashamed. They sought a leader who would redress these grievances because of how American self-confidence and patriotism had been dented by Obama who considered himself Leader of the Free World rather than, first and foremost, President of the United States. This eroded US self-confidence and the nation’s ability to be patriotic without feeling ashamed because, from their perspective, if the President of the United States was not proud to be American then how could the general populous be.

Donald Trump was the person who appealed to this desire for patriotism with the phrase ‘Make America Great Again’ which promised to make America a powerful geopolitical and economic force by cracking down on the outsourcing of jobs and through toughening the US’s attitudes towards Russia, North Korea and Iran so that the US was respected and feared again on the world stage. It could be argued that Trump has achieved tangible results as he has forced North Korea to the negotiation table, got the North Koreans to release three American hostages without agreeing to a swap deal, and held a summit with Vladimir Putin. The response of the Democrats and liberals to Trump’s slogan ‘Make America Great Again’ is that America has never been a great nation, it has a lot to be guilty for, and it represents racism. This has alienated a significant proportion of voters who feel unable to support the seemingly unpatriotic and un-American arguments and positions of the Democrat Party. The perception that Democrats and liberals are not proud to be American has only been perpetuated by their insistence that Trump represents a greater threat to US democratic institutions and world peace than Russia, Iran, North Korea, and ISIS. Furthermore, the refusal of the Senate Democrats to fund Trump’s border wall in the 2018 budget, despite many current Senate Democrats having voted for border fencing in the past, has created the perception they hate Trump more than they care about preserving American security and sovereignty.

In conclusion, Trump’s politics are not unprecedented in American politics and because Trump succeeded Obama, whose victory many hoped signified the ushering in of a progressive era, it could be construed that populism and protectionism is an ideology deeply engrained within US culture. The fact that many Americans believe this form of politics to be unprecedented is a sorry indictment of a profound ignorance they have regarding their own history. Furthermore, as this politics is not unprecedented, it seems likely that the American constitution, the institutions it empowers and the unalienable rights it enshrines (and the Republic itself), will not just survive Trump but endure into posterity, irrespective of whether Trump continues in the White House until 2024 or not.