Little Boxes on the Store Shelf

By Abby Buckland

MA Conservation of Cultural Heritage student

Deep in the Conservation Department Teaching Collection (a collection of almost 1000 items, giving examples of a range of different materials and object types for student conservators to study) sat twenty rather unassuming little cardboard boxes. Overlooked by many, they would turn out to hold a fascinating slice of history.

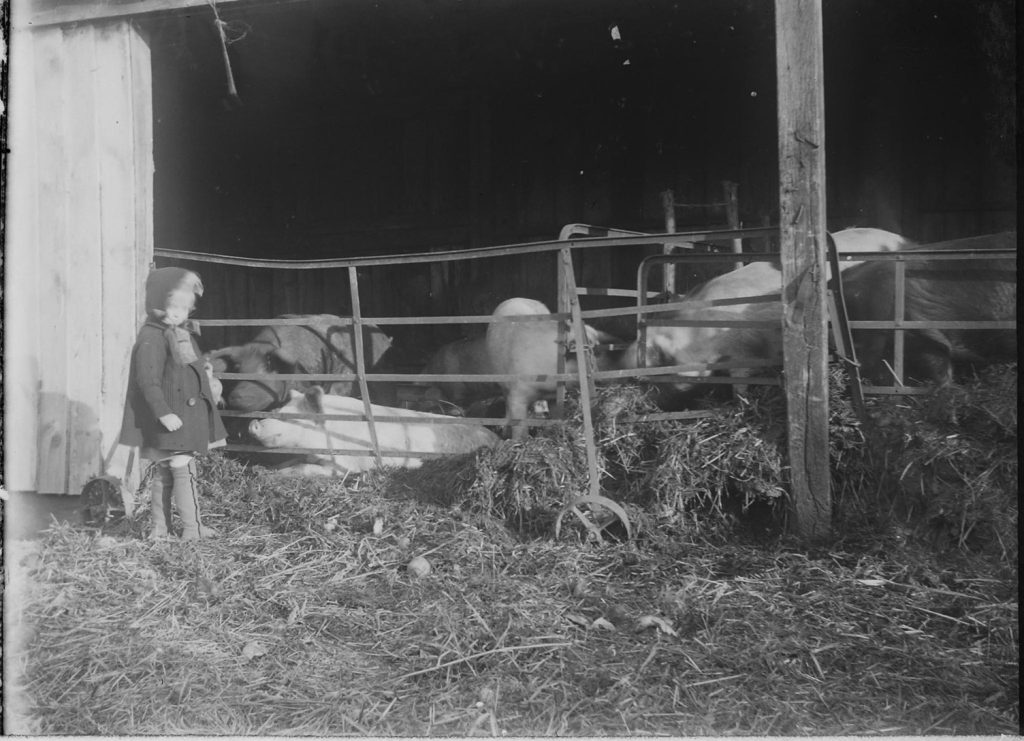

I first encountered the collection in 2022 during a summer internship to re-catalogue the Teaching Collection. Opening one of the boxes, myself and the other student intern discovered them to be filled primarily with glass plate negatives, though envelopes, photographs and film negatives would also be found. Holding one up to the light showed…sacks of beans? Another, beanstalks growing. Another, a farmyard scene with pigs. A look into the rest of the boxes showed a similar story – agricultural images dating back at least 100 years. But with almost 1000 objects to catalogue and store to complete this project, further investigation would have to be left to someone else.

The boxes and contents didn’t really leave my thoughts over the next few months, however, and when the opportunity arose to work on them as part of my Conservation Practice module on the MA in Conservation of Cultural Heritage, I jumped at the chance. Able to sort through everything to assess condition, the agricultural theme continued across all 20 boxes, occasionally interspersed with family photos – both posed and candid. And, in amongst it all, was an envelope bearing a name: ‘A. W. Oldershaw Esq.’ of Ipswich.

History

A name, a location, and approximate dates meant that it was relatively easy to learn more about Oldershaw. Recorded in the 1921 Census as being the Agricultural Officer for East Suffolk County, the subject of the negatives started to make far more sense. With numerous journal articles, a handful of books and endless contributions to local newspapers all being attributed to him, Oldershaw was undoubtedly an authority on all things agriculture. A little further digging showed him to be the recipient of an MBE in 1917 while he was serving as the Executive Officer of the East Suffolk War Agricultural Executive Committee (London Gazette, 1917).

So how did his collection of images end up in boxes in the Teaching Collection stores, a long way from their origin in Suffolk? And what should be done with them next?

The ‘how’, unfortunately, continues to remain something of a mystery. They’ve been a part of the collection longer than the University of Lincoln has existed. The ‘what was to happen to them’ was a somewhat easier question to answer. Though in remarkably good condition for their age, research quickly showed that leaving them as they were, would be less than desirable. With this in mind, the treatment could begin.

Treatment

There are two main strands to conservation – interventive, where objects are directly treated; cleaning, consolidation and adhesion all fall under this category. Then there is preventive conservation, where the conditions surrounding the objects are controlled to prevent any further deterioration; light levels, temperature and humidity all factor in here. As, too, does appropriate storage. And so, the task of creating a bespoke storage solution that would house the original boxes alongside their contents, and slow any further deterioration, began.

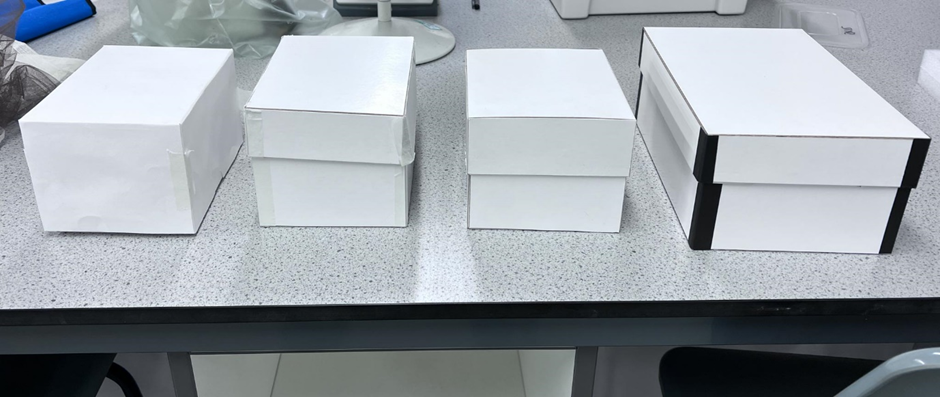

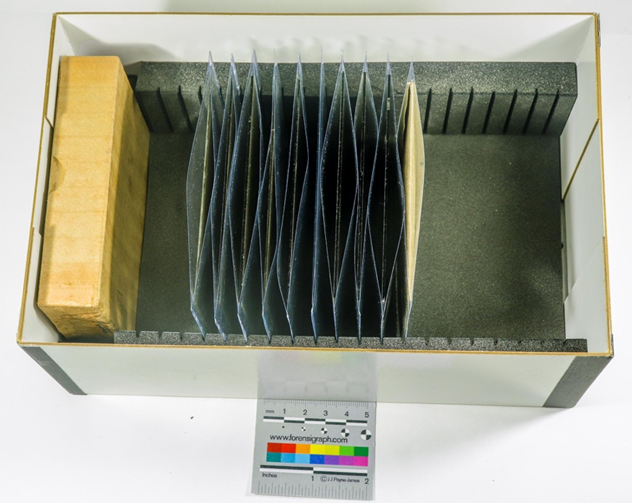

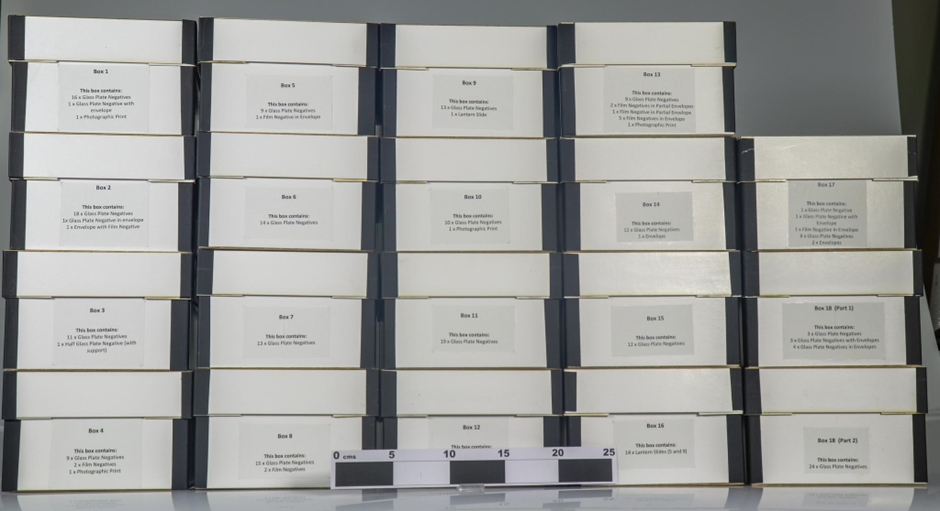

Using paper, a prototype box was made, the design refined by making the lid less deep with the second iteration in mountboard. Adjustments were made to measurements before a third prototype was made, and it was at this point I realised that it would take a very long time to create enough boxes if I were to do so by hand. With the support of the College of Arts workshop within the University, I was able to make use of laser cutters, significantly speeding up the process of cutting out the nets – the 2D flat shape that is folded to make the 3D shape – for 20 identical boxes. The laser cutters were also used to create foam inserts for the boxes, allowing the plates to be fully supported.

With the nets assembled, and corners supported with linen tape, the process of creating over 250 inert (meaning that they wouldn’t react with the plates in any way) plastic (Melinex) pockets began. The Melinex was cut to size, folded and the sides sealed using a heat sealer – this meant that each individual plate would have the appropriate protection from those around it, and would make it easier for handling without having to seek out gloves.

With the corners of those original boxes that needed it consolidated to prevent further deterioration, the four broken plates were supported with specially cut plates of glass to create a sandwich. After that, everything could be sorted into the new storage boxes, and labels put in place to ensure that the contents wouldn’t be mixed up. Not only would the new boxes ensure the longevity of the collection, their uniform size and shape would also make future storage easier – if a little bulkier.

The Future

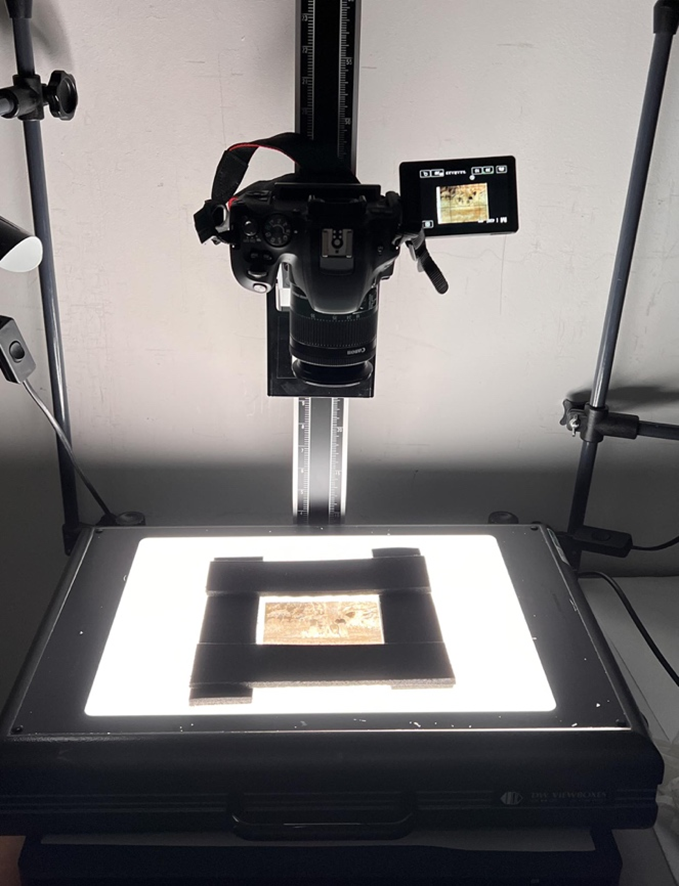

Confident that the collection was unlikely to deteriorate any further, I began to think about what would come next. Though secure in the boxes, most of the value in the plates lay in what the images were of – they needed to be seen. While digitising the images wasn’t part of the treatment proposal for this particular project (to do so for all 256 plates would be very time intensive without the benefit of adding to skills – a key consideration for student conservation projects) a process was, nevertheless, tested as a proof of concept. Using a copy stand, the negatives were photographed on top of a lightbox. This created a digital version of the negative, which could then be processed and inverted using Adobe Photoshop, to create a positive image (as you would get from traditional photographic processing techniques). The results are a fascinating snapshot of rural life in the inter-war period.