By Laurie Rees, BA(Hons) Conservation of Cultural Heritage student

My name is Laurie Rees (they/he) and I am a Conservation of Cultural Heritage student at the University of Lincoln, and will be heading into my 3rd year of study on the BA(Hons) degree in September 2023.

During the summer, students are encouraged to take on extra experience to prepare for the following year of study and their future careers, to explore our interests and develop our skills further. Due to my interest in textiles and craft, a project was bought to my attention by my lecturer, Leah Warriner-Wood, to replicate a fragile museum textile which cannot be put on display.

The object in question is a sun bonnet, made by author D.H. Lawrence’s mother: Lydia Lawrence (Figure 1). Owned by the D.H. Lawrence Birthplace Museum based in Nottinghamshire, it is a key part of their collection which cannot be displayed or handled due to its fragility and deteriorated state.

Lydia made these bonnets herself to provide for herself and her family, the hats being displayed and sold from the window of her house in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire. Made between 1883-87 of printed cotton, a part of the Lawrence family story is unable to be told because of the light damage the textile has been subjected to over time.

The project to replicate the bonnet has been made possible by the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Scheme (UROS).

UROS is a pathway for undergraduate students to carry out academic and research-based projects outside of their university course, but still supported by staff and funding.

I was successful with my application along with my supervisors Celeste Sturgeon (Senior Technician, Lincoln Conservation) and Leah Warriner-Wood (Lecturer and PhD researcher at the University of Lincoln). As a collaborative effort, a plan arose for the approach to this object – to bring the bonnet back to the public eye through physical replication and digital techniques, involving an exploration of making processes of the past, and creating public communication materials for the museum to use. Our final title for the project is: Replicating the Lydia Lawrence bonnet: an ‘experimental conservation’ approach to collections care and public engagement for the D.H. Lawrence Birthplace Museum.

The project began 2 weeks ago and already challenges have arisen but progress has been made with a few helping hands.

The start of a deadline-based creative project is always a time of preparing and wishing you’d had the foresight to have planned more stringently earlier. This is even more true when it comes to Conservation so, put Craft and Conservation together, and you are buried in Gantt charts, and wishing your past self-had been a little more thoughtful about present day you.

Printing the fabric and research into pattern drafting have been the goals of the first couple of weeks. The University of Lincoln have a fully equipped textile printing studio with machines for digital embroidery, digital printing, and most tools you would need to create what you require for fashion, art or, in our case, Conservation.

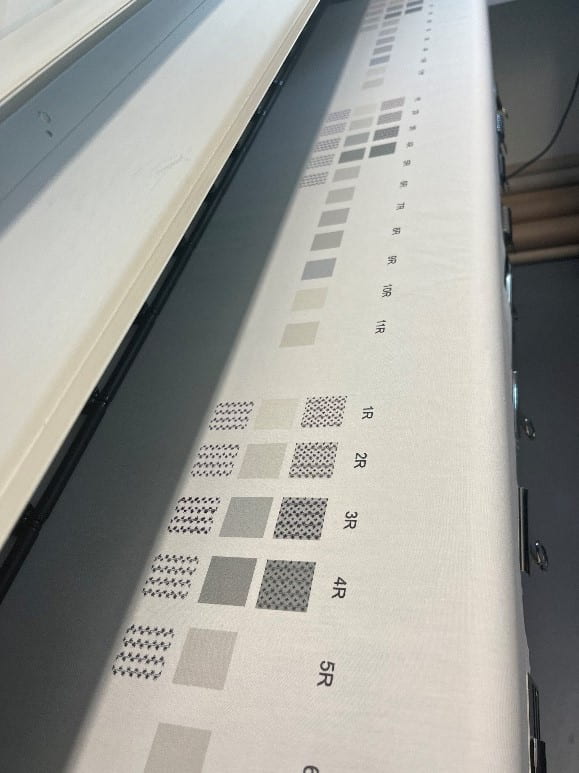

With the help of Polly Lancaster, a textiles specialist Technician for the College of Arts, we used a method of digital reactive dyeing to produce the replica fabric, using a Mimaki Textile Jet Tx2-1600 Digital Reactive printer (Figure 2 and 3). You can find the contacts and materials utilised for this part of the project below as, if you are a University of Lincoln College of Arts student, you can access these facilities.

Polly commented that the Fine Art students here at the University are never too concerned with colour matching but, as conservators, colour matching is a core part of our trade, so we were keen to get it as close as possible to the original.

To reproduce a fabric’s colours, multiple tests need to be undertaken using different tone variations and fabrics. The fabric is then steamed and washed, which impacts the colours further. Overall, it is quite a lengthy process to achieve something you are happy with.

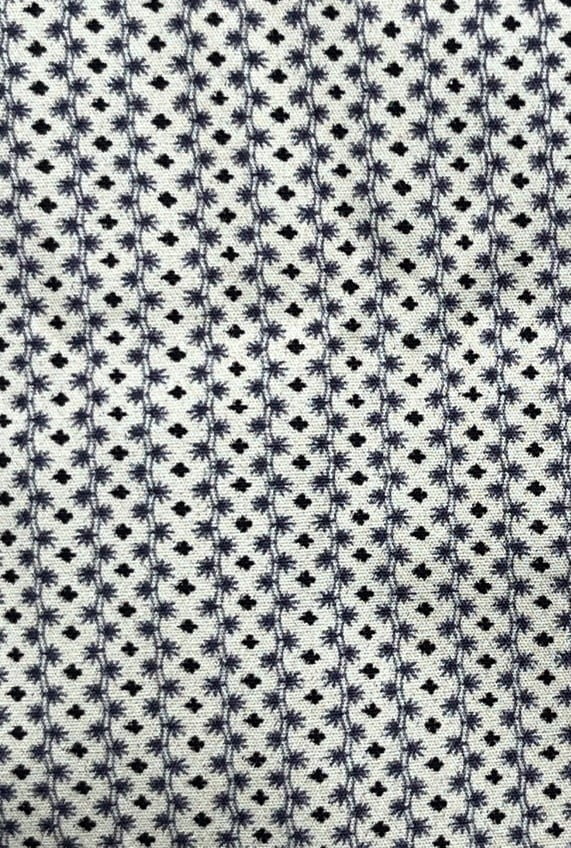

The bonnet is printed with a fine vine and star pattern, most likely roller printed, in a delicate purple and dark blue colour palette on an off-white ground colour (Figure 1). Recreating the off-white is a lot harder than you would think. The variation in whites is astonishingly wide – with the slightest variation in yellow or blue you’ll have the wrong shade. Add in the variation caused by steaming, washing, and age to think about…it leaves your head spinning.

At least I wasn’t alone though. With the help of my supervisor Celeste and graduate Pei-Pei Lee we developed a design for the pattern that is as close to the original palette as could be achieved (Figure 4). I speculate, however, that because of the making processes of the time, the colour of the dyes and fabric would have changed from bonnet to bonnet, from batch to batch, and that washing processes would have altered them with wear, and time. Therefore, colour matching for historic working textiles such as this is perhaps not as scientific an issue as we’d like to think with our perfectionist mindsets.

Now that the fabric is printed, I will be starting to take a pattern from the original bonnet, from which I can sew the replica. More about that in a future blog!

If you are a University of Lincoln student interested in using the digital textile printing facilities, you can contact:

Polly Lancaster, Technician for College of Arts and Studio 27

Studio 27, PDW building