by Erin Fairhurst

Second year BA History and Art History

In January 2022 I was offered the opportunity to apply for an internship programme offered by the Art History programme in collaboration with Lincoln Conservation as a paid painting’s conservation intern for 3.5 weeks.

I am currently in my second year of the BA Art History and History at the University of Lincoln, and in applying for the internship, I was excited to gain insight into the workings of a conservation lab, conservation processes, and to talk to the professionals behind the business to understand their perspectives and the journey to get to where they are now in their careers.

With conservator Rhiannon Clarricoates I looked at paintings closely and discussed the various methods of technical examination using different lighting and light sources. This allowed me to see how the appearance of a painting can shift with a change in the angle, colour and intensity of light, and how this affects how conservators go about retouching paintings. It is necessary for them to ensure that the retouching will not be visible when it is transferred from light in the studio to light in its gallery setting.

During my internship, I worked on a series of blog posts for the Hull Maritime Museum, which would cover the steps of painting’s conservation. I asked for members of the team to explain the steps to me, and it was my job to write this in an accessible way to the public. This was great practice for my writing and gave me a better understanding of what painting’s conservators do step by step.

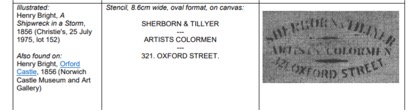

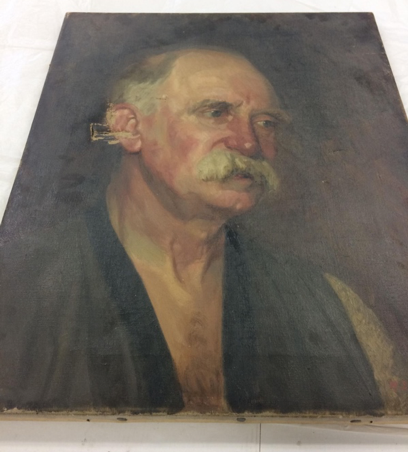

I examined the reverse of paintings and frames for inscriptions, canvas stamps, colourmen labels and gallery labels, which I researched to establish provenance and approximate dates. The two paintings below I dated as being from the late 1850s which I established from the provenance of the canvas stamps on the back. And the style of suit that the man in the smaller portrait was wearing, and the military uniform in the other, which was an 1858 US Union Army uniform. I used smoke sponges to clean the back of the canvas on another painting to reveal their canvas stamps. I also researched the signature, which I was able to trace to being of an artist active 1913-1930: R.S Mayer.

Smaller portrait

Larger portrait

Conservator Paul Croft explained and let me explore the use of a handheld XRF spectrometer, an analytical technique in which the device scans the paint to identify pigments used in a painting, which can be used for dating purposes. For example, if titanium white is present within a pigment, it can be assumed that the painting is likely to have dated after 1900. It can also be determined if toxic substances such as lead, or arsenic are present which determines the safety measures that should be taken when working with the object.

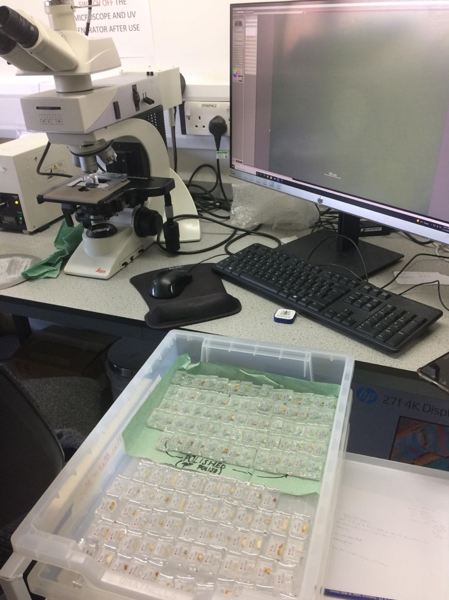

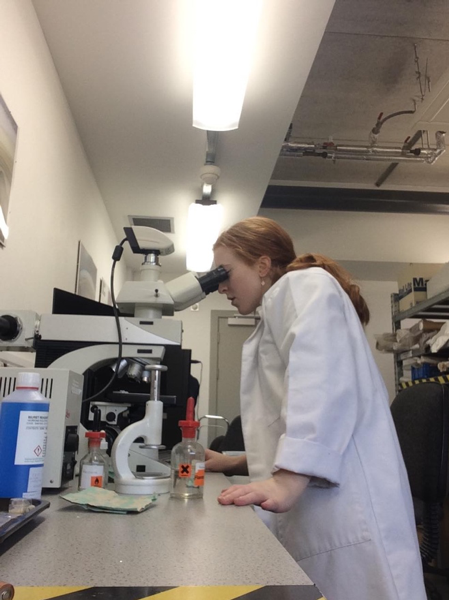

Conservator Celeste Sturgeon explained to me methods of paint analysis. Paint samples are extracted from historic buildings by delicately tapping at the surface of the sample area and flaking off a bit of the paint and the layers beneath. These samples are mounted in resin blocks. These blocks are then sanded down to create a flat edge which shows all the layers. The samples are placed under a microscope at a high magnification, and one by one pictures are taken of every sample. This can reveal the different paint layers that a surface has been painted with over the years. This work is often done when it is intended that a room is to be painted as it would have been originally, and conservators can look at the first layer of paint and see what colour it was.

Rhiannon and I took two trips to heritage sites. The Manchester Town Hall is currently undergoing a huge refurbishment in its ‘Our Town Hall Project’. The focus for the day was to assess the Ford Madox Brown murals in the Great Hall, for any cracks in the plaster that may have developed with age, and vibrations from the building works. I looked for these cracks and consulted diagrams that indicated where cracks were and edited them to show where cracks had worsened since the last assessment for conservators to be aware of for maintenance of the murals. I spoke to some of the crew and asked questions about the work they were doing for the project. You can see me in safety gear up at ceiling level, at the top of the huge scaffolding.

The other visit was to the Burton Constable Hall in Hull to show the head Curator Philippa Wood the ‘chained figure’, that had been conserved and partially restored by Lincoln Conservation. The figure is a replica of a figure seen in the Monument of the Four Moors in Livorno, Italy. I spoke with Philippa about the plans for the museum within the hall and I had a private tour of the rooms that are not accessible by the public, which I hugely appreciated. In seeing and learning about the figure, I decided that I would like to write my third-year dissertation on it, and the monument of the four moors that it replicates. So, this trip was not only helpful for the behind-the-scenes tour of a museum as a work in progress, but also for the great stories that Philippa told me about the reactions to the sculpture by volunteers for example, and its background.

I urge everyone that has the chance to apply for an internship to do so. Whilst painting’s conservation is not the direct career plan I aspire to, this internship was hugely beneficial for my understanding of how paintings are maintained and gave me a new perspective of the importance of the conservation of historic objects at a level where I could see the difference conservation makes to the damage that aging can cause. Next year, I will apply to master courses within the field of museum studies and public history, and it is my aim to work in the heritage sector, so it was beneficial to understand how the work that is done to create the experience of art galleries and historic buildings in which paintings look clean, bright and vibrant through their conservation is conducted.