Amerindian featherwork and the European gaze

by Laura Anisha Bignell

BA art history third year student

The Arts for Equality and Diversity Bursary Award*

The Art and Power in the Renaissance World module of the BA Art History and History course in Lincoln demonstrated how important it is to engage with narratives of inequality in history, so that we can understand the origins of issues such as racism and sexism. Specifically, one of the assessments for this module and contents of this blog post invited students to explore the idea of the European gaze with regard to the way artistic objects made by non-Europeans were described in textual sources. This module has in turn helped me reflect on the society we live in today. With art and architecture as the focus, the module looked at the different ways monarchs and other elites projected authority throughout the Renaissance period. With no limitation on geographic regions, and also engaging with non-elite agency in cultural and artistic production, it also allowed me to research the ways different societies and cultures interacted and reacted to each other.

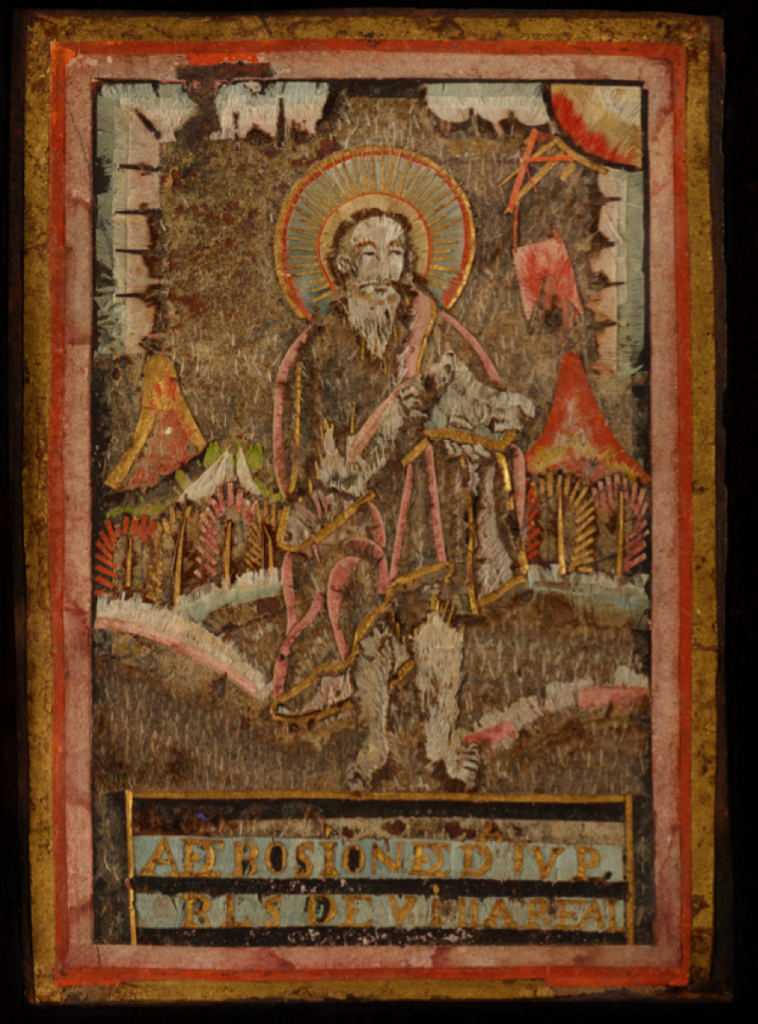

For my assessment, I analysed a letter from 1514 sent by Francesco Allé, an Italian friar working in Mexico, back to the head of the Order of Conventual Franciscan Friars in Italy. After admiring two images of Saints created out of feathers by the indigenous people of the Americas, he wrote that the Amerindians he encountered ‘weren’t literate’, and specifically mentions they do not know how to paint.[1] Without evidence to back up his claims, it is likely the friar is presuming this new culture is less established or evolved. Because they are unknown and do things differently to him, he judges them immediately with a negative gaze. Figure 1 is an example of early 17th century Mexican Featherwork that is currently held in a private collection and something similar to what Allé would have seen at the time. In this kind of artwork, feathers were normally placed on a cotton cloth or board and bonded to it with ‘a certain paste’.[2] The unknown artist used a combination of materials, including feathers, copper, paper, and gold. What is impressive about this piece is its small size. In total, it reaches just 15 x 11 cm. With the precision needed to place each individual feather to create such detail, the artist must have had both great visionary and practical skill. The figure of Saint John the Baptist holding what appears to be a small animal, possibly a lamb, is central to the image and is framed by a decorative border. The background of fields, trees and mountains sit on the horizon line and contrast the vertical axis of the figure. Beneath the saint, gold lettering is framed in a rectangle box below his feet. Although difficult to see now due to the piece being roughly 400 years old, there is some surviving colours or red, gold, blue and green. Fallen prey to time, and the nature of the organic material, the texture has become matted and is likely affecting the shapes seen today, which is why it is difficult to discern the figure Saint John is holding in his hands. Originally, the piece would have had an interesting texture due to the natural fibres and layering of individual feathers.

To his surprise, Allé mentions the Amerindians had a ‘prodigious memory’.[3] Here he is alluding to their ability to recollect images and then render them into unique, bright, and astonishing feather-worked pieces.[4] What is important to him is that they can effectively render the likeness of Saints using a new material to the Italians (feathers from exotic birds) and because of this the pieces ‘are more beautiful than if they had been made in gold or silver’.[5] This quote indicates the value of the featherwork pieces, despite the negative European gaze on the Amerindians as individuals, they cannot deny the significance of their artwork and ability to create something striking out of a complex material. He also says that these pieces are to be bought to Rome to the Pope Paul III, leader of the Catholic Church. For such an item to be given to the highest member of the Church, it reveals the power these pieces had as they were either desired by the highest members of society or deemed appropriate to be given as a gift to them.

The friar in this letter describing Amerindian artists working with feathers demonstrate that the European gaze, which is a term used to describe the perception European people hold over other individuals or cultures that do not fit the ideals of their own, dominates his view of Amerindian artistic ability. This is a damaging narrative that is unfortunately found in many aspects of art history, where one culture negatively views certain aspects of another, just because it is new or different. This idea of ‘otherness’ as presented by the friar can be seen in cases of present-day racial inequality. Through researching the past, we can compare and criticise our own current social and cultural actions. Using information from the material we engage with at the University of Lincoln, we can begin to acknowledge, engage with, and break down the barriers of a long history of racism on our continent and beyond.

* The Arts for Equality and Diversity Award from the BA Art History and History is generously supported by the HR Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Department. This year a series of projects have been selected for the University of Lincoln Festival of Creativity.

Bibliography

Crespo, Hugo Miguel, (ed.) The Art of Collecting: Lisbon, Europe, and the Early Modern World (1500-1800), (Lisbon 2019).

Newhall, Diana (ed). Art and its Global Histories; a reader (Manchester, 2017).

Russo, Alessandra (ed.) Images take flight: feather art in Mexico and Europe (1400-1700), (Chicago 2015).

Primary Sources

Textual source: A letter of c. 1514 sent from Mexico to Padre Clemente Dolera da Moneglia, head of the Order of Conventual Franciscans in Bologna, and other friars of the order found in Diana Newhall (ed). Art and its Global Histories; a reader (Manchester, 2017), pp. 52-53.

[1] Francesco Allé, ‘Letter sent from Mexico to Padre Clemente Dolera da Moneglia head of the Order of Conventual Franciscans in Bologna, and other friars of the order’, [1514].

[2] Hugo Crespo, The Art of Collecting: Lisbon, Europe, and the Early Modern World (1500-1800) p. 350.

[3] Allé, ‘Letter sent from Mexico to the head of the Order of Conventual Franciscans in Bologna.

[4] Featherwork (Saint John the Baptist) Mexico, Early 17th c

Copper, paper, feathers, and gold. 15 x 11 cm

[5] Allé, ‘Letter sent from Mexico to the head of the Order of Conventual Franciscans in Bologna.

* The Arts for Equality and Diversity Award from the BA Art History and History is generously supported by the HR Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Department. This year a series of projects have been selected for the University of Lincoln Festival of Creativity.