By Liam Robinson, Level One Undergraduate

Customs and rituals are important. We mark days, seasons and special occasions in part to celebrate the passing of time. In rural Lincolnshire, the mid-winter holiday has been celebrated for at least three hundred years by the folk custom of Plough Jagging. Groups of mostly male agricultural workers would tour local farms, houses and pubs performing a short play, including dance and song. The performances were often used to solicit donations of food, drink or money – essential ingredients for a celebration! The widespread practice of Plough Jagging in Lincolnshire declined after the First World War as a result of social and technological changes. There were only a few isolated examples still being performed in the interwar period and by the 1950s the practice was largely extinct. During the folk revival of the 1960s to the present, many of the original plays have been brought and performed using scripts collected orally from former participants. These scripts, along with oral testimonies, early twentieth-century photographs, newspaper and court reports of disorder associated with the practice, form the main documentary sources about Plough Jagging.

Although rarely mentioned in the text of the plays, the photographs and oral testimony point to the fact that the hobby horse was an important part of the plough jags’ company. Some anecdotes describe the hobby horses of rival groups fighting and children would often try to steal a hair from its tail for good luck. Given the central importance of the horse to agricultural work, it is hardly surprising that the teams chose a horse as their mascot.

The nature of folk customs and the societies that produced them make it difficult to find physical objects to study. Much of the culture was orally transmitted. It relied on make shift props and costumes which could be assembled from re-used or surplus materials. As a result of this, there is very little physical evidence remaining.

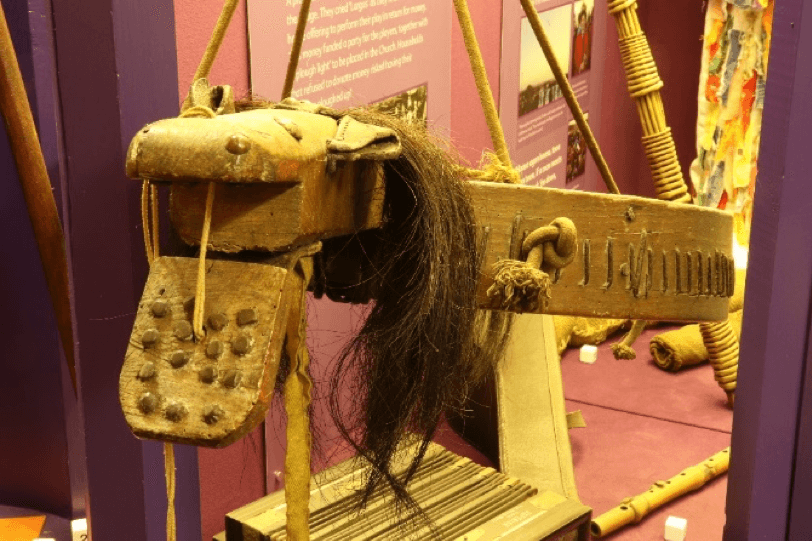

I have a wide knowledge of Lincolnshire folk customs but as a conservation student, I am also interested in objects. My interests converge at the North Lincolnshire Museum in Scunthorpe. The museum collection includes an example of a plough jags’ hobby horse. It is thought to have been used by the Burringham Plough Jags in the early part of the twentieth century. The museum acquired it from the collection of historian and folklorist Mrs Ethel Rudkin, whose work recorded many Lincolnshire folk practices.

The horse is currently on public display and the museum kindly allowed me to examine it.

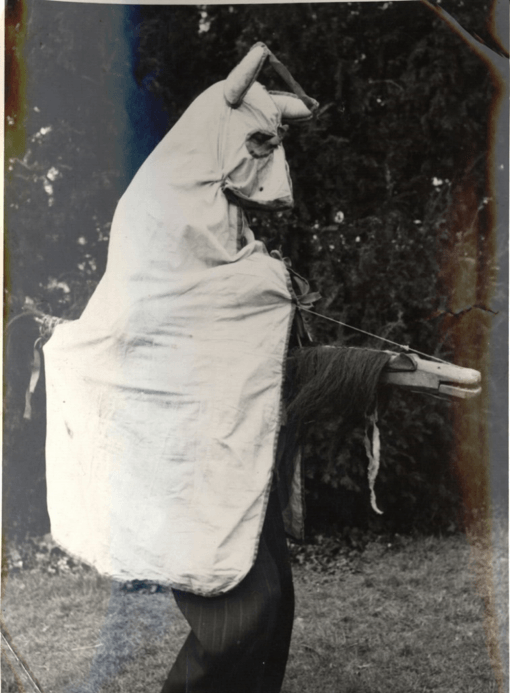

The body of the horse is made from a wooden hoop with a diameter of 60cm and a depth of 10cm. It is possibly originally part of a potato riddle or sieve. The hoop is strengthened by two wooden cross pieces. The horse is designed to be worn around the waist, supported by rope braces over the rider’s shoulders. The rider was then covered with a horse blanket or canvas sheet. The horses head is roughly carved from a 6cm square piece of wood, which protrudes 42cm forward from the ring. It has a snapping jaw, articulated by a leather hinge, which the rider can operate using a string. The inside of the mouth has teeth represented by metal studs and nail heads. This would add to the snapping noise and viciousness of the jaw. Metal studs and nail heads also provide representation of the eyes and nostrils on the top of the head, with leather loops forming ears. The head is completed by a mane of what appears to be real horse hair, held in place by a nailed leather strip. At the rear, a tail protruding 16cm, is made of a small stump of wood which supports another bundle of horse hair.

The materials used could easily be sourced from a farm yard and no attempt has been made to disguise their origins. The horse was created using simple techniques, familiar to most agricultural workers. Simple carpentry, rope knots and leather work were all key skills in pre-mechanised farm work.

There is currently no evidence as to how Lincolnshire hobby horses were animated during performance. However, other existing examples of English hobby horse performances such as the Padstow May Horse (Cornwall) or The Antrobus Horse (Cheshire) point to the idea that the horse was a wild and terrifying spectacle. A rearing and twisting animation with vicious snapping jaw and a heavily disguised operator would make an exciting and frightening performance.

I am not aware of any other preserved examples of Lincolnshire Plough Jag horses. Their make shift and home-made nature means that few, if any, have survived. A surviving example is important, not only as a physical link to our past but also adding to our knowledge of the performance, practice and context of Plough Jagging. By studying the materials, production techniques and visual impact of the horse, we can gain further insight into the world which they inhabited and cast light on folk customs which largely exist in the consciousness of the communities that practiced them.

I would like to acknowledge the help and assistance provided by Eveline Van Breemen, Collections Assistant (Social History) of North Lincolnshire Museum in the compiling of this blog.

Liam Robinson is a first-year undergraduate, studying conservation of cultural heritage at The University of Lincoln.

Edited by Samantha Ann Rose Brinded