By Samantha Ann Rose Brinded – Level 3 History Undergraduate

2018 marks 100 years since the first woman legally held the right to vote in Britain. This occasion has been commemorated by numerous events, exhibitions, tea parties and VOTE 100, a project funded by parliament celebrating this step forward in women’s suffrage. The 1918 Representation of the People Act aimed to reform Britain’s electoral system by allowing the vote to all men (over the age of 21) and women over 30 who met the minimum property qualifications, or at least was married to a man who did. Although this still left out a great deal of women, it was a step in the right direction and after years of fighting, it was considered a battle won for women’s rights.

By celebrating this moment, we remember those who made it possible and immediately names such as the Pankhursts, Emily Wilding Davison and Flora Drummond spring to mind, names renowned and automatically linked to the suffrage movement. However, there were those who came before, those who never got to witness this pivotal moment and yet played a vital role in paving the way for others. This article will look at one of these women, Emilia Jessie Boucherett, Lincolnshire’s own lost suffragist.

Born in 1825, Jessie (as she was known), was the youngest child of the affluent Boucherett family of North Willingham, Lincolnshire. Her father, Ayscough Boucherett, was the High Sheriff of Lincolnshire and descendent of Mathew Boucheret, a French protestant who came to England in 1644 and was created Lord of the manor at Willingham. Growing up, Jessie was educated at the Avon Bank School in Stratford upon Avon. Run by the Byerley sisters, the school counted women such as Elizabeth Gaskell and Effie Gray among its alumni. Part of the school’s curriculum focused on women authors of the day, which undoubtedly inspired Jessie’s love of reading and her own future career as a writer. By 1895 her older siblings, Henry and Louisa, had died, leaving Jessie the sole heir of her family estates. She herself never married and with no direct heirs, upon her death in 1905, her family home passed to distant cousins.

This is only a brief summary of one aspect of Jessie’s life, for she was also a campaigner for women’s rights, part of the Langham Place Group and author. She also founded The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, known as SPEW, which still runs today under the name Futures for Women.

“The plan at present adopted in England for providing for superfluous females, is that of shutting them up in workhouses. It is not very unlike the medieval one of convents, and presents many of the same defects; many women requiring relief being shut out, while the condition of those admitted is one of uselessness and unhappiness, and the waste of good working material is equally great in both cases.”

These words, written by Jessie in her 1869 essay ‘How to Provide for Superfluous Women’, is a stark look at the role of the single Victorian female, by comparing contemporary attitudes to medieval ones, she shows how little progress had been made. She continues with, “It is manifestly unjust that women should be prevented from getting employment and yet be punished for not working.” This view sums up her main concern in the fight for female emancipation, employment. Thus, it is no surprise that in 1859 Jessie founded The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women.

Though somewhat unfortunately nicknamed, SPEW was established on the belief that women should be encouraged to work and thus gain a degree of economic independence. This was achieved by offering interest-free loans to cover the cost of training and starting a school which offered courses such as book-keeping and clerical work. The society’s other successes include sponsoring the first female printing and law-copying business, arranging the first shorthand classes for women and opening up occupations previously only available to men, such as hairdressing, photography and watch-making.

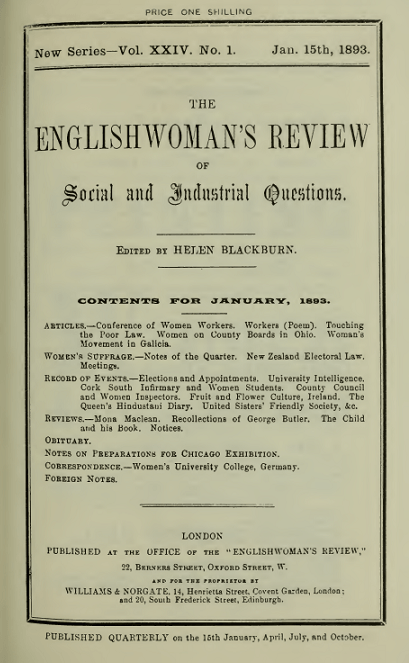

SPEW was originally based at 19 Langham Place, also home to the English Woman’s Journal, a monthly feminist periodical. By 1864, despite financial aid from Jessie, the journal had collapsed but the following year, Jessie had founded its successor, The Englishwoman’s Review. Becoming its first editor, as well as regular contributor, Jessie ensured that the voice of this movement continued to inform and educate well into the next century. Langham Place would also inspire the name for the Langham Place Group, a gathering of like-minded women who campaigned and fought for equality in education. Jessie was a member of this as well as the Kensington Society, a group which successfully drafted and presented the first mass petition to parliament on the subject of women’s suffrage. Among the 1499 names collected are three Boucheretts, Jessie, her sister and her mother.

“Knowledge is one thing, the power of making use of it another”, wrote Jessie in her 1863 book, Hints on Self-Help; A Book for Young Women. Possessing of both an education and independent income, Jessie practised what she preached and used the power of her situation to further her causes. As the sole heiress to a wealthy estate, Jessie did not need to live the life she did. Not only did she help in regards to funding but was actively involved, whether it was public speaking, campaigning or putting pen to paper.

Jessie’s obituary in The Lincolnshire Echo stated that she “engaged in many ways in endeavouring to improve the condition of the weaker sex.” It then notes her charitable work before going on to describe, with some detail, her lineage. In contrast her obituary in The English Woman’s Review read, “she was the brain of all various agencies she either started or joined; the other workers recognise this, and so simple and straightforward was she, that she never thought about herself as leading, she thought of her cause only.” These tributes highlight that though progress had been made, there was still work to be done.

To this day, women still fight for equality in the workplace but it’s because of people like Jessie that I, a female attending university, can look to a future with opportunities and options that women 100 years ago could have only dreamt off. It is the Jessies of this world that promote and invoke change, continuing the fight for the right to exist in an equal society.

For more information go to Futures for Women

UK Parliament vote 100 (Check out thei twitter @ukparliament for daily information and up-coming events)

Books/Essays:

Boucherett, Jessie. ‘How to Provide for the Superfluous Woman’, in Josephine E. Butler (ed.), Woman’s Work and Woman’s Culture: A Series of Essays (London, 1869), 27-48.

Boucherett, Jessie. Hints on Self-Help; A Book for Young Women (London, 1863).

Bridger, Anne and Ellen Jordan. “An Unexpected Recruit to Feminism”: Jessie Boucherett’s ‘Feminist Life’ and the importance of being wealthy’, Women’s History Review 15 (2006), 385-412.